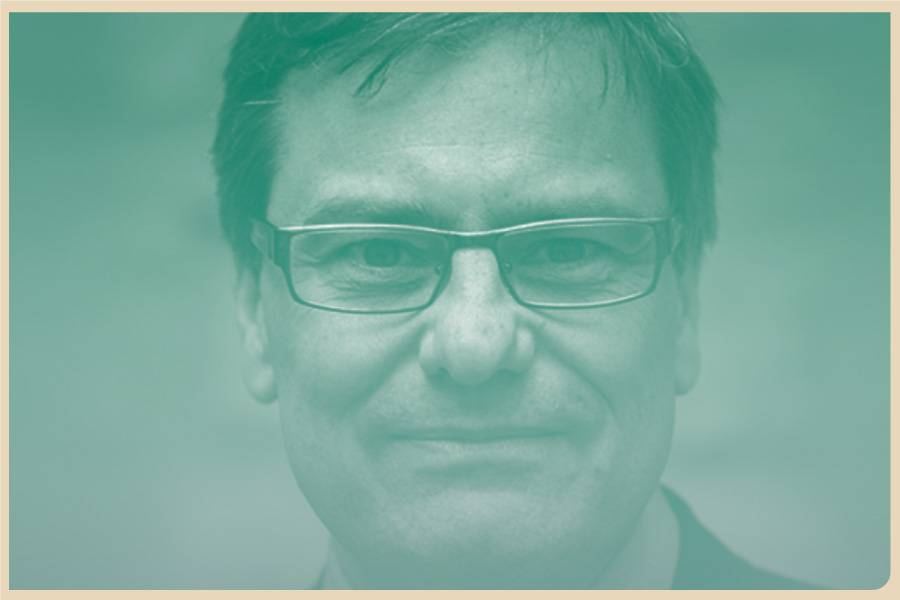

Händel: music, emotions and community | Clemens Birnbaum

Considered by Beethoven and Mozart to be one of the greatest musical geniuses and influences in history, Händel is a composer whose legacy has been rediscovered over the years. In recent decades, different theaters have rescued his Italian operas such as Agrippina or Rinaldo or oratorios such as Theodora or Israel in Egypt as a way to bring the Baroque to new audiences. Clemens Birnbaum, director of the Händel House and the Händel Festival in Halle, Germany, guides us to delve further into the influence and legacy of this composer, a personality essential to understanding the evolution and impact of today’s musical productions.

When Georg Friedrich Händel decided to settle permanently in England in 1712, his oratorios and operas were already beginning to enjoy prestige among audiences in 18th-century Europe. According to musicologists Winton Dean and John Merrill Knapp, attendees at the performances were stunned by the composer’s sublime and grandiose style. “It was said at the time that Handel’s music captured the breath and altered the mind,” wrote Dean, referring to the stage performances at Covent Garden and Cannons.

Handel has the distinction of having written chamber music, oratorios and operas that appealed to both the refined European aristocracy and the middle classes, attracted by the emotional component of his works, the stories of biblical proportions and a majestic musical style in the orchestration.

The popularity of this composer, however, is also marked by enigmas regarding his identity and nationality. University of Wisconsin researcher Pamela Potter points out that Händel “is a figure determined to be included in the pantheon of Germanic composers, but at the same time difficult to consider as a composer of German music.” Clemens Birnbaum, director of the Casa Händel Foundation and the Händel Festival, agrees: “It is difficult to consider Händel as a German composer like, for example, others of the time such as Bach or Telemann. Händel left very early to England to consolidate his career and musical style ”.

In this exclusive interview for Ópera Latinoamérica (OLA), carried out within the framework of the Management of Music Festivals seminar -organized by OLA and the Teatro Mayor de Bogotá- we deepen together with Clemens Birnbaum – who will also participate in the next V International Music Festival Clásica de Bogotá – about Händel’s work and influence on both baroque and contemporary music.

- Do you remember how you got in touch with Händel’s music?

The first time I heard Handel’s music was when he was around 6 or 7 years old. There was a record, an LP with the “greatest hits” by different composers. I don’t remember the particular play, but it was probably the Music for the actual fireworks or The Messiah. When I studied music, I was part of a choir and I have a very vivid memory of representing the biblical oratory Israel in Egypt.

When I studied in Cologne I was introduced more deeply to the music of Händel. This city is central to what we call “historical music production practices”, that is, getting involved with the sound of period instruments and the artistic direction of the Baroque in order to achieve the most faithful representation of this music.

- How did you connect with that music according to your personal tastes?

One of the most famous phrases of the composer Kurt Weill still resonates with me a lot, who said: “I have never recognized the difference between serious music and light music. There is only good music and bad music ”. When I worked at the Kurt Weill Festival I realized that this thought was similar to my perception. I am fascinated by the music of the Middle Ages, the Baroque and the Romantic period, but also contemporary sounds, from the avant-garde to jazz or pop.

Beyond music and going back to Händel, when I arrived in Halle in 2009, which is the city where we hold the Händel Festival, together with other musicologists we delved into Händel’s biography and repertoire.

- And what did you discover?

Starting from, how to work the reception of the public to the works of Händel. But I have learned a topic that is rather political: which composer is promoted or not in the programmatic offer. For example, this can be illustrated by the reception for the works of Bach, who was a very prestigious composer for the Prussians of the time and I feel that his works have a much more massive reception than others.

Händel, however, is not strictly a German composer because he left to shape his career in London, so we can classify him as a German-British artist. But when we remember Beethoven or Mozart, they were very interested in Handel’s music, which was positioned as a very important influence on their respective careers.

So here is a challenge, which is the promotion of extremely influential composers -such as Händel-, but who do not enjoy as massive a programming as they should be.

- What other influences do you see in that political arena?

During the 20th century, Germany experienced two dictatorships after the Weimar Republic. On the one hand, of course, the Nazis, who took it upon themselves to take on different German composers to put together their own narrative and propaganda around Handel’s “Germanization” to rally the masses. I think it’s interesting this politicization of Handel’s repertoire, particularly his oratorios, and how music reflects society and vice versa.

*

In postwar Germany a process of rediscovery and appreciation of Handel’s music developed. In the early 1920s, a movement of musicologists emerged that, among other activities, promoted the German premiere of the opera Rodelinda in 1920. Then, in 1922, a large-scale show was held in Halle: the Händel Festival. . In its first edition, the oratorios Semele and Susana and the opera Orlando furioso with arrangements by Hans Joachim Moser were presented.

The success of the festival contributed to the creation of an institute for studies and programming dedicated to Händel. Among the key characters in the recovery of the composer’s catalog is the musicologist Rudolf Steglich, who, according to Pamela Potter, promoted his music as “more than building society” and instead as “building community”, capable of showing the path away from “too individualistic existence” towards something “new, communal-intellectual-solid.”

In this sense, according to Steglich, Händel’s music would serve as “a remedy for the fragmentation and divisive spirit that Germany was experiencing in the interwar period”, and as a “source to unite a society destroyed by the horrors of the First World War. ”.

*

- Is there any dialogue or reflection between the baroque tradition and modern society?

I would not dare to say a general influence of music on society as a whole. However, I do believe that there is a particular influence on each person on an individual level, expressed in the reception of a certain piece of music. What I mean by this is that, for example, the UEFA Champions League anthem takes a lot of references to Handel and his oratorios. And who is unfamiliar with that hymn!

Regarding how modern music can be influenced by the Baroque, I think it depends on which side you look at it. In that sense, jazz has a lot of connection, because baroque music is based on numerous improvisational passages. And what more characteristic of jazz than improvisation!

Even if we go back a bit further in time, in my opinion I believe that the Baroque came to greatly influence a special generation of German society and culture who wanted to break with the romantic tradition and Wagnerism. In the 1920s composers and musicians emerged who decided to recover the epic of the Baroque. For example, Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex oratorio, which borrows resources such as capo arias from Baroque opera. I think it was introducing a new form of narrative and storytelling opposite to what had been done since Romanticism.

- From a musicological point of view, what should we pay attention to when listening to Händel’s music? What are its essential characteristics?

That is a very good question. If you look at Händel’s catalog, there are many works that we could consider as works in progress or opera in movimento. What is fascinating is the way in which musical arrangements are conceived to achieve an important emotional effect. Handel composed very powerful music using instruments such as trumpets and timbanis. But of course Bach used them too, although the effect is far from the same.

When it comes time to develop the programs for the Händel Festival, we look at the affection we want to convey to the audience. That is why we select arias or oratorios that best reflect that emotional component of Baroque music and of Handel in particular.

- In this context of organizing festivals, how would you suggest reaching audiences or new audiences through Händel’s music?

I think the starting point is to program the most famous works, such as Music for the real fireworks, Music of the water or The Messiah. I would not suggest starting with Handel’s operas as there are many that are quite long and can alienate audiences who are just getting into the lyric. It is much easier to present this genre with oratorios shorter or easier to digest in experience.

On the other hand, there are a number of combinations that can be made between baroque music and modern elements. As an example, it can be combined with jazz for the same reason I mentioned earlier about improvisation. Another interesting mix can be seen in the baroque lounges, baroque music that uses contemporary electronic devices.

Finally, it is essential to keep working with children. You can create stories with them to make the opera more appealing to them. In that sense, many of Handel’s works can be interesting, as they tell stories that can be interpreted from the point of view of a fairy tale.

Opening of the Händel Festival in the market square next to the Händel monument. Photo: Thomas Ziegler

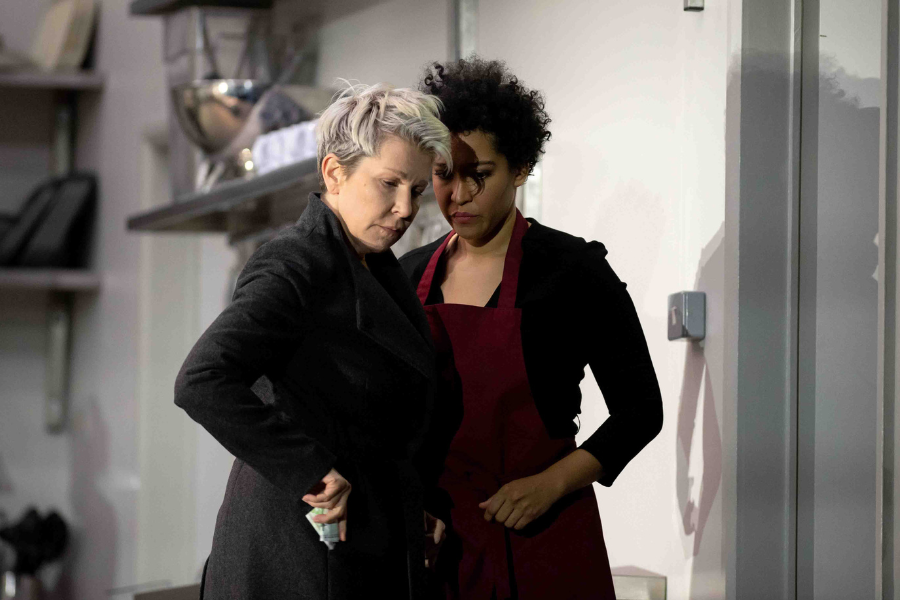

- Baroque operas have recently been premiered with a particularly modern and conceptual staging and artistic direction. I am thinking of the Metropolitan productions for Orpheus and Eurydice or Agrippina. Is that also a way to attract new audiences?

It is not so common to find stagings of baroque operas because they are something very specific. The plot is counted only in the recitatives and the arias are very powerful on an emotional level. It is difficult to set these stories in a modern context, so the artistic direction must be different from the operas that we consider more classic.

Baroque operas, in any case, can have a gesture represented through a règie that deals in depth with theatrical elements and resources. That model can greatly impact audiences. As you say, it can be an interesting crossover between two radically different worlds, the old baroque and contemporary postmodern society. This allows us to search for new forms of dialogue between the two periods and invites us to think of different stagings.

Nor should we forget the emotional component that is typical of baroque opera and that is vividly represented by those on stage, be they singers or dancers. If you look at the way Rinaldo was produced in London, it had a spectacular array of assets like small fireworks, dragon puppets popping up on stage, shocking! I think there is a certain magic with which you can work these exciting baroque compositions and, of course, Handel’s.