Àlex Ollé: Expanding taste and questioning public certainties

Known for being one of the founders of La Fura dels Baus, the artistic director Àlex Ollé (Barcelona, 1960) had a new adventure in the world of performing arts in 2022 with the Òh!pera project. The initiative, organized jointly by the Gran Teatre del Liceu and the Barcelona City Council’s Design Hub, consisted of transversal work between young people from different disciplines to create a micro-opera that would address current themes and lead to a new operatic experience. In De opera y otras herbes, Ollé recounts this experience and provides ideas on broadening the taste of regular audiences, deepening musical education and the reflections behind the reinterpretation of an opera in today’s world.

By Alvaro Molina R.

Cover photo: Daniel Escale

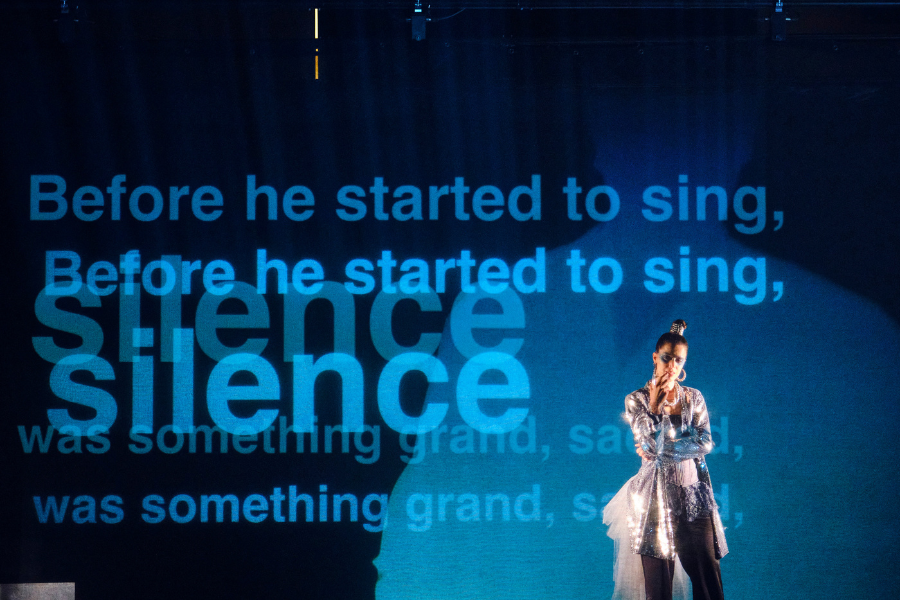

It is July 2022 at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, in Barcelona. A post-apocalyptic setting in the information metaverse contrasts with the classicism of the Hall of Mirrors. At the Conservatory, meanwhile, a disturbing Gothic story of ghosts and spiritualism explores the causes and dangers of misinformation and casts a shadow over the theater of the Conservatory. The Liceu foyer is, at the same time, the setting for two works: one that recounts the mistrust between couples and another that freely and updatedly adapts the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

All the above pieces are part of the Òh!pera project, an initiative promoted in 2022 by the Gran Teatre del Liceu and the Disenny Hub of Barcelona City Council. In charge of the artistic direction is Àlex Ollé (Barcelona, 1960), known, among other things, for being one of the founders of the theater company La Fura dels Baus. “In projects like Òh!pera, we can see operas of very different musical styles, with stagings designed from risk and a desire for innovation, and with a very extensive range of artistic and aesthetic languages that undoubtedly reflects the many paths that exist in contemporary creation”, says Ollé. The artistic director worked with four teams each made up of a composer, librettist, stage director and a Barcelona design school to create a new 30-minute opera addressing contemporary themes.

The fruit of this project were the operas Entre los árboles, composed by José Río-Pareja, with a libretto by Juan Mayorga and stage direction by Nao Albet; L’occell redemptor, composed by Fabià Santcovsky, with stage direction by Marc Chornet; The Fox Sisters, composed by Marc Migó, with a book by Lila Palmer and stage direction by Silvia Delagneau; and Shadow. Eurydice says, composed by Núria Giménez-Comas, with a libretto by Giménez-Comas and Anne Monfort and stage direction by Alícia Serrat.

Social networks, misinformation, climate change, violence and more

Discovering new talents for opera was one of the goals of (Òh!)pera. How did you put together the creative teams?

Òh!pera is a project that wants to provide opportunities and, in this sense, all of us who are involved in one way or another aspire to is to contribute to the emergence of a new generation of professionals. Because we must not forget that opera is, in essence, a multidisciplinary art. And in every opera you need composers, librettists, stage directors, musicians, singers, set designers, costume designers. And also illuminators, props, councilors… and a long etcetera.

In the Òh!pera project we formed four teams, each made up of a composer, a librettist, a stage director and a design school. Each team performed a newly created opera of 30 minutes maximum duration that they jointly developed until the premiere.

The first to be selected are the composers and it is the artistic director of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Víctor García de Gomar, who is responsible for doing so. Later, the composers choose their librettist. And it’s up to me to select the stage directors. To do so, I base myself on works that I have seen from each one of them, on references, recommendations and, at the end, on an interview.

With regard to the librettists, we only ask that the scripts deal, as far as possible, with current issues and that may interest a younger and more heterogeneous audience.

What characterizes the new talents that were chosen to create the micro-operas?

Deciding who has talent is not the purpose of the Òh!pera project. We aspire to give all those selected the opportunity to enter the world of opera. And, as an objective of the project, to generate a new group of young creators. Also, and very importantly, that through their work they attract new audiences.

As I have said before, the selection of composers and stage directors is made from the work they have done before. What matters is the personality that these jobs show, the capacity for innovation and, also, the capacity for risk.

From the musical side it is perhaps easier to see these generational characteristics, due to the use of electronic music, the fusion of musical techniques, the way of using the instruments or the way in which they explore the properties of sound.

But when it comes to stage direction, it is more complex to determine those characteristics. Perhaps the way of using the stage space is one of them: breaking the fourth wall in many cases, with the audience standing, moving through the space like the singers. Another could be a greater relationship between singers and musicians. And, finally, everything that has to do with the aesthetic currents of this moment.

(Òh!)pera was proposed as a reflection of the current moment in Barcelona in the field of composition, in which new generations have emerged, trained in a renewed cultural and historical context and inserted in the global environment. In artistic and aesthetic terms, can you tell us about this current moment in the city in terms of creation?

The composers selected for the first two editions of Òh!pera are part of the Barcelona Creació Sonora project in which, apart from the Gran Teatre del Liceu, other musical institutions and the city council also participate. This type of program responds to the need to provide an outlet for the large number of musical creators that exist in the city so that their works not only do not remain in a drawer, but also reach the programming of large venues and, therefore, so much to the general public. Which is perhaps the bridge that is sometimes missing in the field of contemporary music.

We are at a time when composers have very broad, hybrid and multidisciplinary formations and, therefore, the range of styles of newly created works is very wide and it is not easy for the programming of the major facilities to reflect this great variety.

That is why projects like Òh!pera are necessary, where we can see operas of very different musical styles, with stagings designed from risk and a desire for innovation, and with a very extensive range of artistic and aesthetic languages that undoubtedly reflects , the many paths that exist in contemporary creation.

One of the entities that promoted this initiative together with the Liceu is the Disseny Hub Barcelona, a meeting point for innovation, dissemination and experimentation. What are the benefits for a theater of allying with institutions of this type?

Òh!pera was born from the will of the Barcelona City Council, through Disseny Hub and the Gran Teatre del Liceu. Both started from a previous premise which was for both institutions to work together on projects capable of promoting talent and creativity in the city of Barcelona. In the DNA of the project was that each of the productions had a design school in Barcelona. This would be in charge of working, together with the stage director, the conception of the stage space, the set design, the costumes, the video in case there was one, the lighting, etc.

The benefits of this project are for the students of these schools, who will be able to have a professional and practical experience in the process of creating an opera. They will be able to live a creative process from its beginning to the end. And also, and very important, teamwork. Disseny Hub is in charge of selecting these schools.

Now that some time has passed, what is your assessment of (Òh!)pera in general and of the projects that were presented?

The will is for this initiative to continue over time. At the moment, we are already preparing a second edition that will be held at the beginning of July 2023. All of us who have worked on the project are very satisfied with the result. First of all, due to the quality of the four proposals, all of them very different.

The reception from the public and critics was very good. All functions are filled. A very heterogeneous audience came, from the regular audience at the Liceu to young people who don’t usually go to the opera. But just as important is the experience that all the participants in the project had: composers, librettists, stage directors, musicians, singers and students from design schools, etc.

Reactionary aesthetics

On June 23, 1996, the Plaza de las Pasiegas, in Granada, was packed with different audiences. As described by the Spanish newspaper El País, “people of learning, followers of ‘whatever takes’ and, for the most part, a simple public without prejudices, arrived at the place, willing to participate in any event they consider important.” The event in question was the premiere of a new production of La Atlántida, the opera that Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) left unfinished and that was later completed by his faithful disciple Ernesto Halffter (1905-1990).

The expectations were high, since, although the opera had already been on the scene in Granada before, this time the production was in charge of La Fura dels Baus, the Spanish theater company that since 1979 was causing something to talk about in artistic circles. of the world for its creative force and variety of interpretations. After the presentation, fifteen minutes of applause and an ovation “corroborated the excellent impression caused by his excessive visual reading of Manuel de Falla’s most complex score,” the newspaper La Vanguardia noted at the time. For its part, El País affirmed “Never has a production of Atlántida surpassed in imagination and invention parallel to that of the Fura dels Baus”.

The minds behind that stage version were Carlus Padrissa and Àlex Ollé, stage directors and two of the six heads of the founding team of La Fura. Since 1979, the company has opted for eccentricity, innovation, creative force and transgression in its works and artistic adaptations. Over time, the concept of “Furero language” was born, the one that breaks the “fourth wall” between the performance and the public, by transferring the works, be they stage art, opera, cinema or macro-spectacles, to non-public spaces. conventional as a slaughterhouse, a hangar, a jail or a factory.

“The total work of art” coined by Wagner is present in the soul of the Fura. An expression that, according to Ollé, “without our knowing where it came from, we used it to define the type of shows we wanted to do.” La Fura’s proposals mix primitivism and technology, nature and technique, in addition to multiple scenic disciplines in the same artistic melting pot to create a total spectacle. In the world of the 21st century, that diversity of formations is recognizable in the Òh!pera project. “The youngest creators have found themselves with such a markedly multidisciplinary language at a time when composers have very broad, hybrid and multidisciplinary formations”, reflects Ollé.

What effect has the presentation of micro-operas had on audiences? Do you think that opera becomes more accessible to disaffected audiences when it talks about the present?

I think that for the regular public at the Gran Teatre del Liceu it has been very positive to discover composers and stage directors with proposals that are very different from what they are used to.

For many young people, on the other hand, this has been a first approach to the world of opera, which means the discovery of a language characterized by being so markedly multidisciplinary. As Mr. Wagner coined, opera is the “total spectacle”, something that has always amused me, because this expression, without our knowing where it came from, we used when we were very young, to define the type of shows that we were looking to do or that, in fact, we did at La Fura dels Baus.

Also very special was the fact that the four plays were performed in different spaces of the theatre, with the consequent tour of various places in the Gran Teatre del Liceu.

And, regarding whether opera becomes more accessible, the essential thing is, without a doubt, to create scripts with which young people can feel identified or simply interested in the themes they deal with. And also because of the way these issues are approached on stage.

In an interview for The New Barcelona Post in June 2021, you commented that: “You have to produce works that speak to us about the present. In the end, those of us who have done it, and although the local critics have not understood us, we are the ones who have gone out into the world.” What are the issues that occupy or concern creators today?

Many of the issues that occupy and concern today’s creators have not changed in the last hundred years, because most of them are inherent to the human being. But there are others that are more current. They are those with whom, at this moment, we are most sensitive. For example: the way we relate to each other, social networks, the excess and manipulation of information, climate change, violence in all its facets, corruption, inequality, the invisibility of people with functional diversity and, a very important, the anguish of young people for the future that awaits them.

All these topics, and many more, are the ones that should be the backbone of a good part of the proposals for opera and theater scripts at this time. It is essential to provoke in the public a reflection on all these issues.

In today’s cultural ecosystem, is it possible for the creative heritage of opera –whether with traditional, contemporary or experimental interpretations– and new creations to coexist in the same space?

Of course, this is already happening in many theatres, although in most there is still very little commitment to new creations and experimentation in the operatic genre. The opera audience remains somewhat conservative when it comes to stage proposals and contemporary music.

I believe that it is essential that this diversity exists in the programming of a theater. As I have said before, the taste of the regular public must be broadened, but it is also necessary to deepen the musical education of children, provoke the interest of adolescents and attract the public between 20 and 30 years of age. Only in this way will we ensure that opera continues to be a current and future language.

Now taking into account the public that is most assiduous to this genre, what are the proposals to broaden their tastes?

We are many stage directors who seek to update the scripts so that the public can feel more connected with what happens on stage. Sometimes, to create greater interest in the work, we create parallel dramaturgies to enrich aspects that, over time, have lost the value they had when the piece was released. To develop our proposals, we use the stage space in a less conventional way, we use new technologies, or we incorporate video projections to enhance visual or narrative aspects that would otherwise be impossible to do.

Why do I tell all this? Because this way of understanding a staging often clashes with the tastes of a part of the public that is a regular at opera. But only by betting on this type of proposal, without this meaning ruling out others that may be more classical, supporting newly created operas and betting on projects like Òh!pera, we will be able to broaden the tastes of a significant part of the public that goes to the opera. There is nothing that enriches more than diversity, whatever the field.

To what extent can works be interpreted or reinterpreted in opera?

It is a very reactionary aesthetic position to consider that there is a correct way to stage an opera and that this way consists of faithfully illustrating what the text demands. Perfection would consist, then, in making all of them equal or as close as possible to an absolute ideal.

But there is no better exercise than watching productions from 20, 30, 40, 50 years ago… The stagings get old, they turn to papier-mâché, the costumes are ridiculous, the reading is flat… Art is part of of the living world, it is in movement, it changes, it looks for new forms, new ways.

Not even the perfectly scheduled music is exactly the same. Not because each musical director brings his own point of view, but because it also changes how the public listens. And change the repertoire. What lasts does so precisely because it is put to the test.

People go to the theater because they like life. You need to feel questioned in your certainties. He needs to be surprised with an unexpected twist. He wants to see how someone rediscovers, reinvents what is well known.